info@owensfuneralhomeny.com

Isaiah Owens staged his first funeral at age 5, burying a matchstick in a casket made from an empty beer can lined with toilet paper. As he grew older, his passion blossomed and he began to hold real funerals, including one for a neighbor’s beloved dog. While others found Owens’ curiosity with death and its traditions unnerving, the Branchville native said he had simply found his calling in life.

It is that calling that has made Owens the subject of a documentary honoring African-American funeral traditions. “I am excited and really humbled that this has come to pass at this particular point in my career, while I’m still alive, and after all of these years of sacrifice and hard work,” the master embalmer and restorative artist said.

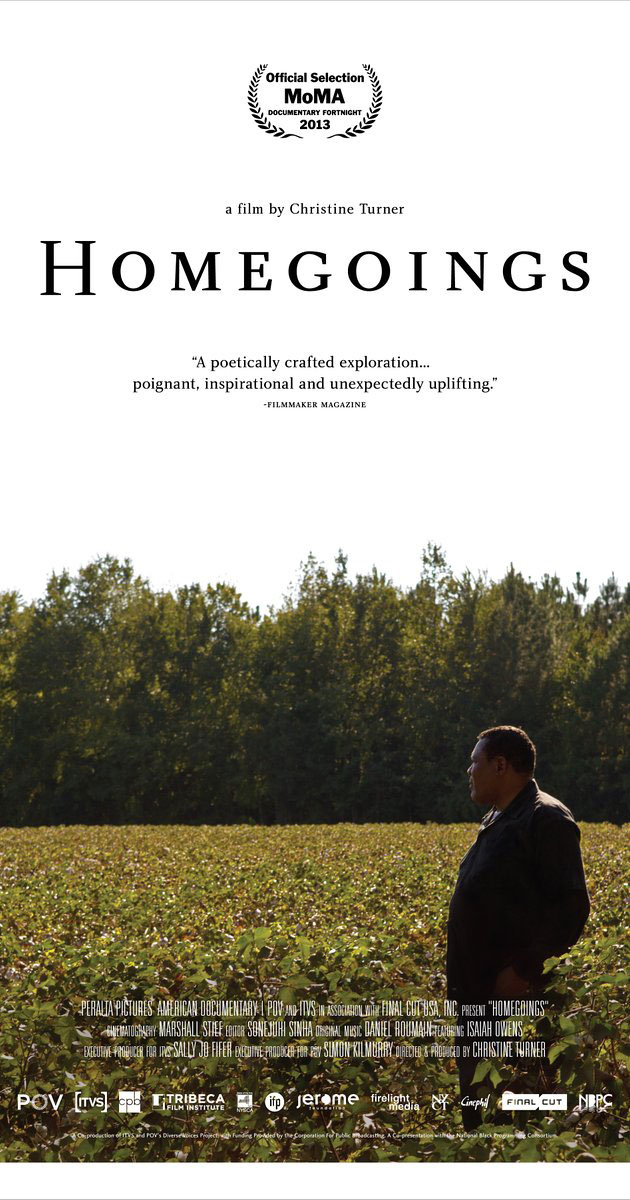

“Homegoings,” the debut feature documentary from New York independent filmmaker Christine Turner, explores the culture and history of death and mourning by blacks, as told through the eyes of Owens, owner of Owens Funeral Home in Branchville and Harlem, N.Y. The film had its world premiere during a screening Thursday, Feb. 28, at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. “Homegoings” will be featured in the International Selections section of “Documentary Fortnight 2013,” the MoMA’s annual showcase of recent nonfiction film and media.

The documentary is also part of “MoMA Selects: POV,” an homage to the Public Broadcasting System’s longest-running showcase for independent nonfiction film.

“Homegoings” will make its broadcast premiere on PBS’s “POV” this summer. “This represents death coming out of the closet, because in the documentary, you’re faced with the fact that you’re going to die,” Owens said. “And for those people who have lost loved ones and look at the documentary, they’ll be able to sit and cry for those people that they’ve probably needed to cry for a long time ago.”

Owens said he hopes viewers also gain a sense of their own mortality, and that the realization leads them to express their wishes while they still can rather than leaving their grieving loved ones to make those final decisions.

“African-American people died with the belief in the resurrection, so the excitement over the resurrected body is one of the things that really kinds of helps,” he said. “As a Christian person, I believe that Jesus Christ died and was buried and resurrected. I think he took the sting out of death at that particular time for me and other people.

“Although death is not something I want to run into this second, I’m aware of Christ’s presence with me as I even go through death.” The filmmaker said she contacted Owens after reading an article about him in The New York Times. Turner said she was intrigued by the man who has spent more than four decades not only caring for the dead, but for those left behind, as well.

“As he began to tell me more of his story, I became further intrigued and realized that there was a making of a film here,” Turner said. “Death is something that’s so taboo in our culture, and I thought that this could be a really interesting way of bringing it to the forefront.”

The film harkens back to a time when blacks were refused service at white funeral homes and subsequently had to find ways to honor their dead. In the film, Owens demonstrates the historical traditions among African-American undertakers, who took pride in caring for their own. “What I love about what I do is having the ability to watch the people speak about my service for them,” Owens said. “It’s their joy and excitement at a time when it should be just the opposite.

“When your grandmother or your mother has been stricken with cancer and winds up being 60 pounds and unrecognizable, how nice it is to walk in the funeral home and see her back at 250 pounds and looking glamorous and fabulous?”

While restoring complimentary features to emaciated cases is among the handiwork Owens performs for the dead, he is also described in the film as a superb caretaker for the living.

“For the 10,000 funerals that I have conducted, I have 10,000 families that pretty much love me and ... will always cherish in their hearts the feelings that I gave to them at the time that was most difficult for them,” Owens said. “When you come to me, I’m gonna take care of you and fix your broken heart. I don’t know how it happens, but I just kind of know the things to do.” Turner said Owens sees his job as serving the living and the dead.

“I think that’s what makes him so exceptional,” she said. “He’s a really warm person who’s great with people.”

It’s a family business, where Owens is joined by his wife, Lillie, and two of their six children, Isaiah Christopher and Shaniqua.

“Lillie has allowed me to become who I am. She never second guesses me,” Owens said. “I spend an awful lot of time working in the business, and she never hounds me and actually works right with me. She’s probably my greatest asset.” Another daughter, Lauren, has just applied to mortuary school. “She’ll do good, and, hopefully, they’ll be able to keep this business around,” Isaiah Owens said of his children and the funeral home he began in 1970, after moving to New York in 1968 to train as a mortician when he was 17.

Turner finished filming the hour-long documentary in 2012 after almost four years. Part of the film was shot in Branchville, where Owens’ 96-year-old mother, Willie Mae, still works two days a week at the funeral home.

“It’s so special for me to still have her. I feel extremely blessed,” Owens said. “I’ve seen so many people in my career who lost their mother at a young age. To see her still getting to work and transferring the calls back to New York is just a blessing from the Lord.”

Turner said “Homegoings” helped her develop her own voice while giving one to family members who lost loved ones in the film.

“The funeral services that I covered in the film tended to be more celebratory in nature. They’re really about celebrating the life of a particular person. I always saw them as a combination of both sad and happy, but also cathartic,” she said. “Death is a universal thing. There’s a way that people can connect with it. Even if they come from completely different backgrounds, there’s a familiarity. “The best films often reflect back on the audience. It was important to really give voice to the people in the film, because ... the experience of talking was very therapeutic.”

Turner said she is honored to have her “passion project” featured at the MoMA’s “Documentary Fortnight.”

“I felt a strong sense of responsibility in protecting the subject matter, so I wanted to do the film with as much respect and dignity as I could. That was always my goal,” Turner said. “I also wanted to show that this has been a tradition in the community for a very long time. “Making the film constantly reminded me of the preciousness of life. We’re so involved in our work and everything else that’s going on that we don’t often stop and just remember how lucky we are to be here.”